Sea level rise is firmly on our radar as one of the major consequences of climate change. As the science improves and climate models become more accurate we are becoming increasingly aware that no matter which way we look at it, sea level is rising and will keep rising into the foreseeable future.

As part of a climate altered future, high sea level extremes will become more frequent – as a rule of thumb for Australia, every 20cm of sea level rise increases the frequency of a particular height being exceeded by a factor of ten.

This means that even a modest rise in sea level would mean that events that happen only once a year now will happen every day by 2100, and 100 year events would happen annually.

Under these circumstances, issues that are becoming pressing for Local Government in a changing climate include:

- disruption to council services

- loss and damage to community owned infrastructure

- loss and damage to privately owned assets

- planning requirements for future public and private

development - • council liability for the outcomes of planning decisions.

Dr John Hunter, a sea level rise authority at the Antarctic Climate and Ecosystems Cooperative Research Centre (ACE CRC), says that the challenge in assessing the risk to our existing and planned coastal assets is to account for the ‘uncertainty’ in sea level projections.

The urgent question confronting development all along the coast is how much higher will high tides, storm surges and floods be, and how much more often will extreme events happen?

Sea level rise heightens the need to ensure that planning procedures account for risk as well as uncertainty. The central issue is deciding how much risk – and associated cost – we’re prepared to accept for our coastal infrastructure under rising sea level conditions.

“Traditionally, planning and building in the coastal zone has relied on data from historic observations of sea level as the basis for projecting how often a certain sea level will be exceeded,” Dr Hunter said. “Underpinning the approach has been a notion that the sea level has, and always will be, static.

“For example, the ‘100 year return period’ guidelines or similar alternatives assume a static sea level and that extreme events – such as very high tides – in the future will have the same magnitude and frequency as they did in the past.

“We are now seeing that this approach is flawed. We are discovering that sea level rise brings with it a ‘multiplying factor’ on conditions at the coast.

“Not only will sea level rise raise the average sea level, it will also increase the frequency of ’extreme events’ – storm surges and severe wave conditions at the coast driven by strong winds, storms and cyclones.

“By 2040 sea level will reach around 0.2 metres higher than in 1990 and extreme events will happen nearly up to 10 times more often. Some of the basic assumptions in our planning codes no longer stand up.”

Looking ahead, what is now a ‘one in 100 year’ event will soon be a ‘one in 50 year’ event, then a ‘one in 20 year’ event and so on.

In asset life terms, this ‘multiplying factor’ significantly influences what we can expect for our coast under new climate conditions. It means that design tolerances for our coastal assets need to allow for risk of significantly more frequent inundations.

Incorporating these new concepts into risk assessments has become a top priority for coastal governments, infrastructure owners, developers, tourism operators, emergency services, real estate and insurance agencies, to name a few.

A central element is deciding on the ‘golden numbers’ for future sea level to incorporate into local and regional planning, building and assessment calculations.

Dr Hunter said that while using internationally agreed figures for projected sea level rise is a starting point, integrating these projections with information on the local sea level history is the key to a proper and robust assessment.

As part of his research at the ACE CRC, Dr Hunter has recently produced a new method of incorporating the internationally agreed projections of sea level rise into local scale planning codes.

It involves statistically combining recorded variations in today’s sea level (from tides, storms and other meteorological events) with projections for future sea level rise. The outcome provides the probability that an asset will be flooded once, or more, during its lifetime.

The technique can be used by engineering and planning authorities to set prudent risk guidelines for coastal developments and infrastructure maintenance.

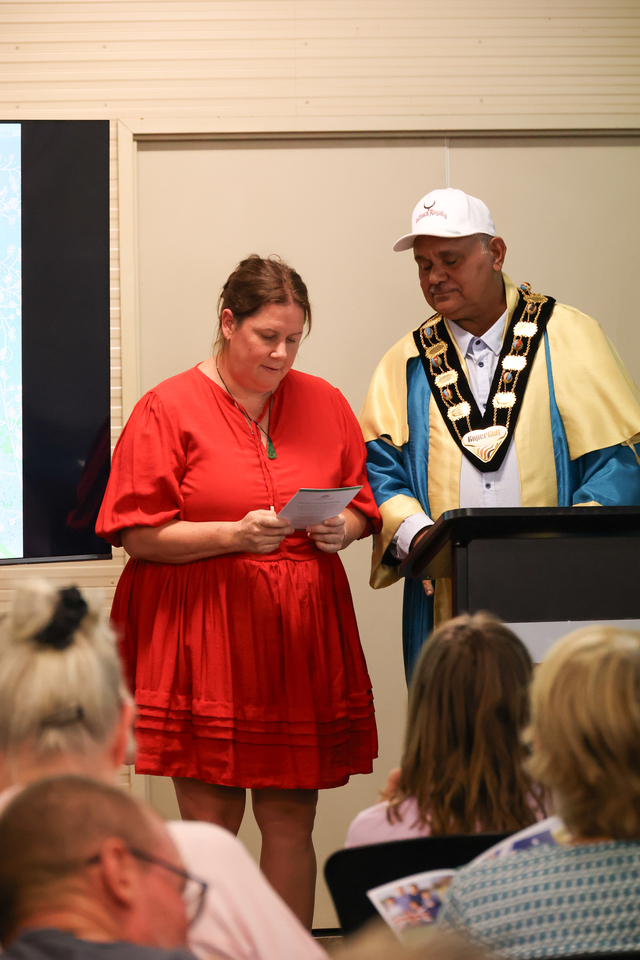

The ACE CRC, with funding from the Australian Department of Climate Change, is providing this information via a web based tool, initially delivered in a national series of free training workshops.

Dr Hunter says the popularity of the courses and the overwhelming support by the State Government and municipal community underscores the need for tools such as this one, to assist infrastructure and asset managers in local decision making under new climate conditions and a rising sea level.

ACE CRC Deputy CEO, Tessa Jakszewicz, says the response to the seminars and workshops has far exceeded expectations.

“There is clearly a strong need for assistance in how to plan for these changes,” she said. “Coastal infrastructure owners and planners realise there is a problem but aren’t sure how best to tackle the issue.

“The web tool has been extremely well received by councils as a first step – but councils are still seeking further assistance in integrating tools such as this, into planning policies.

“The ACE CRC hopes to provide ongoing support through more programs, such as this one.”