*By Allan McGill

While all spheres of government realise the need for process, far too often process can take control of what was well intentioned policy and strangle it to the point that it fails. The consequence is that people and places miss out.

Indigenous policy is one area that clearly needs to be streamlined.

The Aboriginal people of Australia continue to be the most underprivileged Australians, and their housing, health, education and employment are in many cases third world.

Despite, or perhaps in spite of good intentions, innovative policy initiatives and a desire to improve these conditions fail more often than not.

The case studies that follow are specifically related to Aboriginal communities and show how process has highjacked good ideas and strangled the good intentions that were attached to those ideas.

Port Keats

Port Keats, or as it is now known, Wadeye, is part of Thamarrurr Regional Council. This community is the subject of a Council of Australian Governments (COAG) trial that was meant to ensure a whole of government approach in coordination and planning, resources for programs and an effort to avoid duplication and to better deliver much needed services.

The pity is, the good intentions behind the COAG trial have been washed away and consumed by a sea of red tape, process and compliance.

An independent report released in late 2006 identified that ‘departmentalism’ dominated service provision, and that the local Council carried a greater burden of administration than it had before the trial began in March 2003.

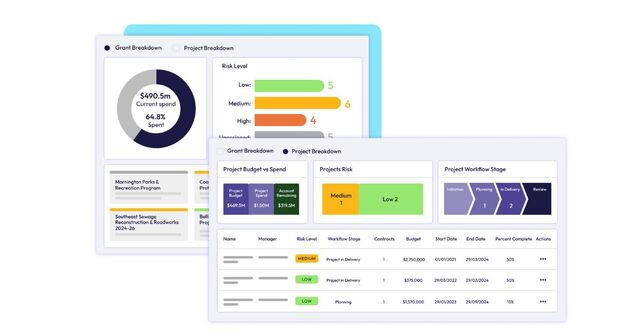

Thamarrurr Council has had to acquit and comply with up to 90 different grants, all of which require different forms and styles of acquittance.

Even within one department there can be different compliance and acquittal requirements. You would think that perhaps as part of a trial like this there could be one common acquittal form or process.

The enthusiasm to pump money into this community failed to have regard to the community’s real needs and the Council’s capacity to respond.

In 2001/02 prior to the COAG trial, Council had $2.9 million in unspent government grants. That figure had grown to $9.7 million as at 30 June 2006.

The range of constraints facing Council include a lack of capacity to action funded projects and an inability to recruit staff for funded positions.

Darwin City Council

Here in Darwin, we initiated a project that involved a shared responsibility agreement between Council, the Northern Territory Government, the Australian Government and the Gwalwa Daraniki Association.

Gwalwa Daraniki is an Aboriginal association that has a lease over crown land in the heart of Darwin and operates two separate town camps, or as they are more correctly known these days IULA (Indigenous urban living areas).

In accepting a role in Aboriginal issues, Council put together a proposal to waive rates due to it and to employ six residents as full time Council employees.

The scheme involved some extra cash from Council, Commonwealth money and Territory funds.

The employees would work on the two living areas, other land controlled by the association, and on regular Council works projects.

The matter was first raised with other governments in July 2005 and although there was some interest, it took months before there was verbal commitment.

A project brief was subsequently circulated and further meetings held. In good faith, Council employed the six people in April 2006.

This project was all about making use of various government programs and Council resources to get a shared outcome that would deliver improved living conditions for residents.

As at February 2007 there was still no signed agreements on the deal, but one Australian Government department raised concerns that some of the employees were earning too much money with Council and that was affecting their ability to attract CDEP funds. These funds were the Commonwealth contribution to the project.

Although the project struggled on, the level of frustration experienced by me was such that I doubt that I will ever be involved again.

Good intentions and a will to achieve something were frustrated by inflexible and drawn out processes.

The Northern Territory is currently going through a reform and restructure process that will see a large number of rural community Councils amalgamated into large Shires.

There is no doubt that reform is needed, but what is in the new arrangements and what the benefits will be is yet to be really known and understood.

One can only hope that what is planned for the new structure, and what is proposed in the way of legislative change, will not create more layers of planning, reporting and compliance obligations. The benefits of this would be largely problematic.

It is important that the new Councils have the financial and other resource capacity to be viable.

They must now become more flexible and allow for local solutions to local problems.

The application process and the compliance reporting process must also be simplified.

Councils must be careful about taking on funds or accepting government grants that don’t fit with their own plans and should ensure that they do not subject their residents to excessive or over the top processes that will irritate and frustrate them.

*Allan McGill is the CEO of Darwin City Council