Australia’s local government associations are carrying $345 billion worth of civil infrastructure on their balance sheets today, equivalent to $14,000 for every man, woman and child in Australia.

That’s a huge responsibility – and one that is set to grow, according to the 2018 National State of Assets report, published this year by the Australian Local Government Association (ALGA).

The ALGA has been encouraging councils to participate in a voluntary self-assessment survey of their infrastructure performance and management practices since 2012. About three-quarters of local authorities are doing so.

That has revealed the scale of the task, and also some of the key problems councils face.

Here are some simple examples:

1) According to the report, old kerbside infrastructure built in the ’60s and ’70s does not meet Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) requirements. For this reason alone, it needs to be upgraded when those assets are due for renewal, inevitably at a higher cost.

With a large proportion of the Australian population entering the older demographics and therefore facing a time of more limited mobility, this will become a growing safety and equity requirement.

2) The ALGA cautioned at the time it released the report that, despite increased investment to renew bridges and the continued effort of councils to extend the life of their ageing assets, the backlog of bridges in poor condition remained largely unchanged.

ALGA President, Mayor David O’Loughlin, said, “Councils are doing their best to bring these bridges up to a reasonable condition, but this report shows that the scale of the problem is beyond the current resources and revenue streams available to councils.”

3) The report also found that, while asset- and risk-management plans are mandatory documents – essential for each council to report infrastructure funding needed for the next ten years – the requirements for asset-management plans are not consistent Australia-wide.

4) There is no link between asset-management plans and funding. The authors argue that this makes a coordinated and effective approach to national infrastructure planning harder.

All of this adds up to a daunting challenge for councils, who typically deal with a wide array of asset classes, registers and systems – ranging from water, road and bridge infrastructure to buildings, parks and gardens, car fleets and construction machinery – reflecting multiple silos in their business.

Without an enterprise view of assets, condition, risk and funding strategies, councils cannot make enterprise decisions. With fragmented data, no one is ever really sure which one is the right version of the truth.

There is little wonder that asset management is rapidly emerging as a top agenda item for local councils – particularly since the introduction of AAS27, the new accounting standard for local government financial reporting.

The standard requires local councils to report not just on the size of their asset bases, but also their value, condition, and lifespan.

That increased need for transparency and accountability creates new pressure points for council managers. On top of that, many councils find the problems of managing their ageing physical infrastructure are compounded by the reality that their asset lifecycle management software reflects an ageing technology infrastructure.

Often these technology systems are themselves reaching end-of-life and they struggle to reflect contemporary realities.

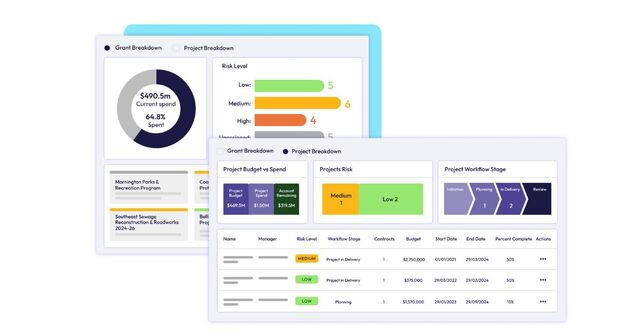

A contemporary solution must allow councils to manage long term asset strategies, such as future treatment planning and integrated asset accounting practice. This allows managers to make better and more informed evidence based asset investment decisions. It also needs to include reporting capabilities that enable leaders to communicate complex engineering outcomes to stakeholders in a simple, streamlined way.

Given the scale of assets on the balance sheets, financial managers in councils also need tools that allow them to manage projects – from prioritisation and optimisation all the way through to delivery.

The savings are significant. Toowoomba Regional Council, for instance, was able to generate savings equivalent to $2.5 million per annum via better strategic and operational asset management, delivering a two percent improvement in depreciation.

And for front-line staff, the solution needs to facilitate asset and work management – for instance, from call centre requests through to work scheduling, maintenance and completion.

An effective solution also needs to reflect the realities of how field staff work in an increasingly mobile world. Work crews and contractors should be able to accept and complete work in both a connected or disconnected environment.

The scale of the asset management problem is set to grow, but how well equipped are your systems to meet these new requirements?

If you’re looking for better business intelligence to help deliver improved services – or simply need an enterprise solution that adapts and evolves as you do – speak to TechnologyOne’s Local Government team about our OneCouncil SaaS solution today. To learn more search OneCouncil Effect.

*Copy supplied by TechnologyOne